The Lensmann from Orkdal

How a rural police chief cut the red tape that could have derailed my life

This post is the first of five in a series inspired by Nolan Yuma’s:

“A support group for people who have to deal with bureaucrats.”

Nolan’s call to action tagged me along with other travellers including

M.E. Rothwell from Cosmographia

Michael from Brent and Michael Are Going Places

Lloyd from the writing grove

Chris from Chris Arnade Walks the World and

Yolanda from Yolo Intel

Check out Nolan’s post which lists a number of others you may want to follow for stories or travel, and maybe, just maybe, bureaucracy…

High school graduation in 1978 is but a blurry, foggy memory, probably because the 70s were, for various reasons I won’t get into in case my mother reads this, a blurry foggy time.

Less than a week after I graduated, and probably half-hungover from the celebrations that started a few months before the official ceremony, I landed in Norway on what was meant to be a gap year, but ended up becoming the start of my four-decade-long European adventure that included thirty-one years at a company that didn’t want to hire me.

Landing in a foreign country as an 18-year-old was a sobering experience that rapidly turned into a sink-or-swim situation that would end in life or, if not death, having to face my mother’s “I told you that you weren’t mature enough” proclamation if I gave in to what seemed a hopeless situation full of homesickness.

Giving up or giving in is not something that comes easily to me.

A couple of months into the school year, as I was overcoming my worst bouts of homesickness, and I began feeling cockily confident that I would make it, the school principal came to class and asked me to come with him.

“The police are looking for you!”

I’m not sure why he felt the need to tell the entire school in a voice that made it sound like I was a fugitive. In the hallway outside the classroom, he handed me over to another, larger, stronger, younger male teacher and told him to drive me to the police station in the nearby town. It felt like I was being arrested, but fortunately, they didn’t handcuff me.

At the police station, I was shuffled into the office of the “Lensmann” himself. In rural Norway, that is the equivalent of the Chief of Police and he oversees a district usually comprised of several smaller communities.

The Lensmann didn’t immediately share with me the grounds on which I had been called in. He asked when I’d arrived in the country, what I had done before school started, and how long I intended to stay. He asked why I came, and why I chose Norway. After confirming I had distant relatives in the country on my father’s side of the family, he asked if I’d met any of them.

It felt like an interrogation but, to be honest, I wasn’t being questioned in a room with a single table, a two-way mirror, and a bright light shining in my eyes that turned my oppressor into a simple silhouette. We were in a comfortably decorated office and his voice and demeanour were friendly.

I diligently and honestly answered every question as well as I could. We were having a nice chat and getting along well when he told me that he had orders to deport me.

“Your passport allows you to remain in the country as a tourist for three months. It allows you to be a tourist. It doesn’t allow you to go to school. It doesn’t allow you to work, but your problem, in addition to being enrolled in a school, is that you have overstayed your visit. I’m supposed to ensure you’re on a plane out of here as soon as possible.”

There was my mother standing at the bottom of the steps to the airplane again….

He asked me why I hadn’t applied for a student visa before I came. My honest answer was that I had no idea. My brother had a Norwegian gap year in 1975-76 so I probably knew or should have known about the visa thing. I didn’t mention that my final year of high school was a blur in far too many ways that likely clouded my planning sufficiently to forget to include a visa application in the process.

“My guess is that you don’t want to be deported”, he said.

Smart guy.

Him, not me.

He also said that he didn’t view me as a great risk to people, property or anything else in his district of jurisdiction and that, unlike me, he had a plan.

“I’m calling Oslo”, he said.

Oslo, being the capital city, isn’t someone you can call, but the Immigration authorities were located there and they had phones. Not everyone in Norway had a phone in those days.

He called. I didn’t understand everything he said, but I got the impression he was on my side.

At one point he broke off the conversation and asked me when the last day of school was. I told him the date. He looked a bit dismayed after relaying the information. His voice rose and the stern look on his face gave me the feeling he wasn’t hearing what he wanted to hear. I was worried and hoped my ignorance, forgetfulness, and stupidity would be enough to earn a verdict of not being accountable for my actions. My fingers were crossed and, despite my lack of religious conviction, I was praying for leniency when he finally hung up.

“I told them it was my fault,” he said.

Apparently, visa applications were sent to the local district Lensmann for review and to check that they matched the enrolment list at the school. He had told “Oslo” that he had forgotten to return mine to them. He made up a story that the application had been lost in the shuffle of all the papers on his desk and filed away in a cabinet full of criminal records.

They didn’t buy the explanation, he told me, probably because they would have expected to have a record of the application that they forwarded to him, but he had convinced them that I was a harmless kid.

They agreed that if he could produce the application he said he had, they would allow me to stay until the end of the school year. I would then have six days to pack up and leave. He said he had tried to explain that I had relatives in the country, and wanted to visit them and do some sightseeing. That didn’t fly with the authorities that already said they were cutting him a break.

Not half as big as the break he was cutting me, but still.

“Don’t worry”, he said, “you can always apply for an extension.”

That advice would come in handy later.

He searched high and low in his office to find the appropriate form. In those days, of course, it wasn’t something you could just download and print off.

To my astonished relief, this local police station, which I am certain would almost never have any use for a blank visa application form, had one. He helped me fill it out and it was duly back-dated to support his story.

We used different pens to make it look like it was filled out at different times in different places. He even scrunched it up a bit to make it look older but he stopped short of spilling coffee on it to make it look even more neglected during its time in his office.

He was having way more fun than I was. I was still worried about what was going on. I was well aware I was lying on a government form but I didn’t know how serious that was when I was doing it at the behest of the Chief of Police.

In my 18-year-old mind, that was a risk worth taking.

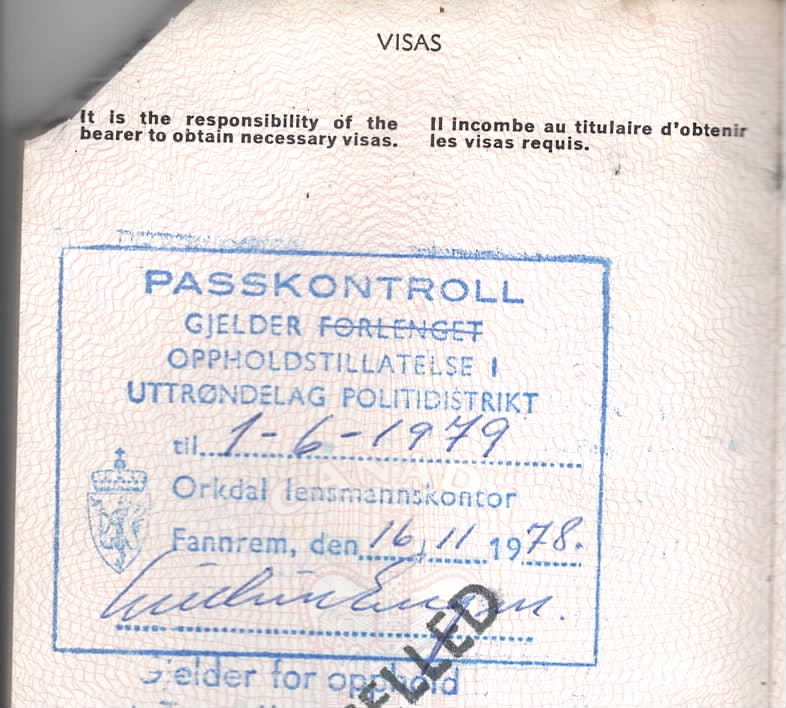

November 16, I was summoned to the police station again. “Bring your passport,” they said. The desk officer stamped my passport and I was given permission to remain in the police district until June 1, 1979, a week after the school year ended.

(In English, visas like this often use the term “Leave to Enter” and I always wondered about that. If you bear with me and subscribe to my writing, someday I’ll tell you the story about the time my wife literally had to leave to enter Canada.)

I was unaware of how the Lensmann’s actions would allow my life to take the path that it did from that point onward. Unfortunately, I have no idea who he was. I do know that I am extremely grateful.

The experience taught me a huge life lesson.

In times when persons of authority often seem to thrive more on wielding their powers under the “just applying the law”, this man had looked at the bigger picture.

What is the risk, he thought? What would his country gain by deporting me? What would the consequences be for me? Should he just follow orders? Should he do what he had the right to do, or should he do what he felt was right, even though it potentially could have had consequences for him?

He chose the latter and he changed my life. In other stories, I will show some examples of how I contributed to the country that allowed me to stay. You can then judge whether you think he made the right decision.

All I know is that had this happened in 2018, there’s a 99.9% chance I’d have been deported.

The Lensmannen from Orkdal changed my life by doing what he felt was the right thing, instead of just following legal protocol. Later in life, a friend of mine introduced me to a saying he had learned that reflected this kind of thinking:

“No one can give you permission to do the wrong thing, and you don’t need permission to do the right thing!”

Stay safe, Always Care

87 stories are part of the Always Care Community, where we share memories, experiences, and lessons learned at the “University of Life”!

Thanks for reading and for supporting my work.

Please connect to learn more about how our experience and expertise can support you, your team, and your business.