"Sink-or-Swim" or "Fake-It-Till-You-Make-It"?

Survival Strategies of an Ill-prepared 18-year-old in a Strange and Foreign Land

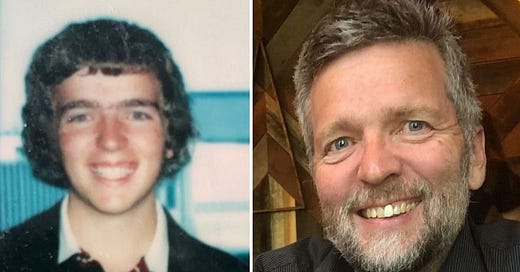

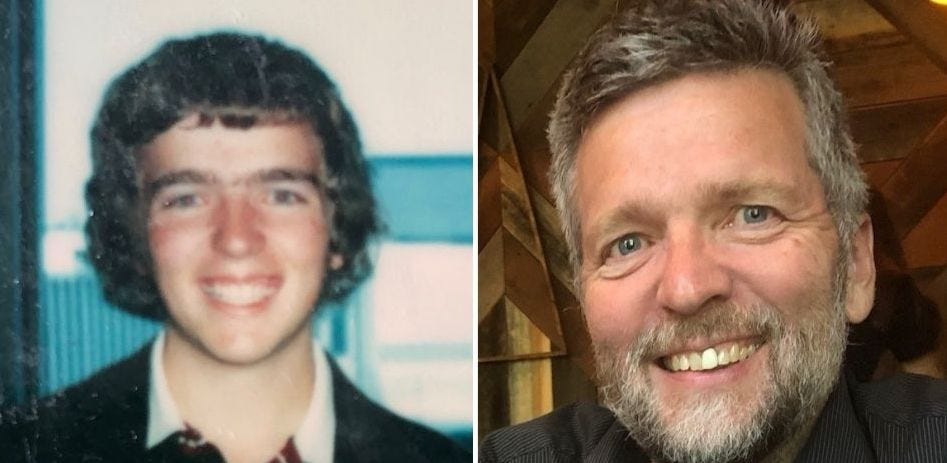

I was eighteen when I graduated from high school. Between us, although I enjoyed my high school years immensely, they are still a bit of a blur. In any case, I’m not really sure I fully awoke from the hangover of my high school graduation party until I landed in Norway. My post-high school gap year began less than a week after I’d donned the KSS cape and climbed the stage in the old arena to collect a diploma that didn’t have my name on it.

It rather quickly dawned on me that Norwegians in Norway spoke Norwegian every day, all the time. All the Norwegians I had ever met in Canada spoke English and although I knew they had their own language and even learned a bit at a language camp, I was unprepared for the fact that when in Norway that’s all Norwegians did. They spoke it quickly. They spoke it with swearwords, slang, and dialects you won’t learn at evening school. Even the little kids spoke it. It was a huge, unexpected shock.

Language families can be related and sometimes it feels like you can simply bluff your way through by pronouncing your language’s words with the correct foreign accent. A literal fake-it-till-you-make-it approach.

Not long after I arrived in Norway, I went to a post office to buy stamps for postcards. (For the younger generations, a postcard was a small paper picture you wrote on the back of and sent to people through the mail before the internet and social media.)

“Jeg vil ha STAMPER, takk.” I confidently said to the person behind the counter. She looked at me like I’d just said “Hand over the money.” I was undeterred and explained in my best Norwegian that I would like some “stamper” (‘er’ at the end of a word often makes it plural in Norwegian, just like the “s” in English does.) Finally, and probably just before she pressed the silent alarm button, I caved, switched to English and asked for stamps. She rolled her eyes, I paid for the stamps and on my way out I saw a big sign that said “Stamps” in Norwegian, English, French and German….. The Norwegian word was “Frimerker”… not even close.

Fake-it-till-you-make-it is an often-cited path to success. It’s not always a guaranteed path… I had faked it and failed, but I wasn’t ready to give up.

In the pretty far North of Norway some people that I had been staying with dropped me in the middle of nowhere where a gravel driveway met a paved road. They said it was a bus stop. There was no sign or timetable but shortly after they drove off, a bus came along and picked me up. I threw the backpack that contained all my earthly belongings into the hold, climbed on board and bought a ticket to Fauske, from where I would catch the night train to Trondheim.

90 minutes into the 5-hour journey, the bus boarded a ferry at Lødingen. Everyone had to leave the bus and go up to the seating area on the boat. When the ferry docked in Bognes, I retraced my steps down the stairs to the car deck. The door was locked. I pushed it. I pulled it. No dice. There was no one else in the stairwell. Behind the door, I could hear vehicle engines start and, even worse, the clank-clank sounds of wheels hitting the ramp told me they were driving off the boat. I ran back up the stairs, across the seating area and down the stairwell on the other side where, thank goodness, the door to the car deck was open. My brief relief was rapidly replaced by fear. As I emerged from the stairwell, my bus was nowhere to be seen. There was only one bus left on the car deck. Same colour, same company and same destination. I boarded it and avoided the stares from all the people who didn’t recognize me.

My mind was racing. Should I approach the driver? What if he didn’t speak English? Worse, what if he threw me off because I didn’t have a ticket for his bus? I decided to wait and hope things would sort themselves out when we reached Fauske. I was a thousand miles from anywhere and everything I owned was on a bus that I wasn’t on. In my mind, less than a month into my gap year, my life was ruined.

Somewhere along the road, the bus stopped at a roadside gas station and café. Refreshment and toilet break. I was probably hungry and probably could have enjoyed the relief a trip to the washroom would have given me, but I was young, had a strong bladder, and I was convinced that I would starve to death as a penniless, paperless foreigner in the middle of Norwegian nowhere if I didn’t get my backpack back. We pulled into the rest area. We weren’t alone. There were other beige buses bound for “Fauske” parked in the lot. While my fellow passengers were eating, drinking and, no doubt, peeing merrily, I went from bus to bus. On the second or third attempt, I hit the jackpot! There was still time before departure, but I had found the seat I’d occupied before the fateful ferry ride and there was no way I was moving until we reached our destination. The other passengers threw me some odd glances when they re-boarded but I pretended they were invisible, just as I had been for them on the leg of our journey that had brought us from the ferry to the rest area.

The night train from Fauske to Trondheim was a nine-hour-long ride from somewhere in the pretty-far-North to somewhere in the a-little-less-far-North. Seating was not pre-allocated. The rusty, reddish-brown train had two seats on either side of a centre aisle. I found a window seat with an available aisle seat beside it. No need to ask permission, I simply sat myself down uncomfortably on a rock hard seat. My backpack was safely stored on the rack above my seat.

From time to time, the train stopped at the small towns along the route. People disembarked. New people boarded. Some saw the empty seat beside me and asked: “Er det ledig her?” to which I politely replied: “Nei.” They all just shrugged and moved on. Must be me, I thought. I was unshaven, probably foreign looking, and after the stress on the bus, I feared my deodorant wasn’t holding up. After four or five people declined what I thought was a polite and generous offer, I smelled my armpit, but no, this morning’s deodorant was more Irish Spring than Moxness stress despite the day I’d had.

As dawn arrived, (not exactly true since this took place in the summer when it was daylight more or less all the time) we stopped in Steinkjer. People disembarked, new people boarded. A spectacle-wearing guy in his twenties spotted the seat beside me. “Er det ledig her?” Going against all common sense and intuition, I responded: “Ja”. He sat down.

The payphone dime dropped. (Sorry kids, Google it.)

I had learned a new phrase. “Er det ledig her” didn’t mean “is this seat taken” or “is anyone sitting here” or anything whereby a negative answer would be interpreted as a positive result for the person asking. It meant, “Is this available?”. That experience burned itself into my brain alongside the fear of meeting any of the multiple people that I had turned away from the vacant seat who, in my nightmares, all froze half to death sitting on the floor between cars on the train during the long ride to Trondheim.

In 1978, Norway was still an emerging market. Then, like now, it had a good education system. What it didn’t have was a lot of money or the Internet. Money would soon start rolling in, but the internet hadn’t been invented. Although everyone learned English in school, it wasn’t common in day-to-day language and most Norwegians never needed to use it. Unlike the angelic, self-sacrificing people of perfection my romanticized upbringing had taught me about young people in my forefather’s land, the reality was they were teenagers. Just like teenagers anywhere. When I started school, most were too shy or too insecure to speak any English. The teachers were kind, the kids were kids. I was me and I was homesick.

After school, the kids would hang around together. They all had tobacco and cigarette paper. In 1978, everyone smoked but only rich people bought filtered cigarettes in Norway. Everyone else rolled their own.

It’s weird when you are somewhere and don’t understand the local language. It’s nice weird because you can just zone out to the buzzing background noise and find zen-like meditation without having to have a mantra. It’s frustrating weird because when people laugh, cry, yell, or scream you have no idea why. It’s absolutely, horrifyingly paranoiac weird when, amidst all that buzz of sound, you recognize your name. Especially when it is followed by howling laughter.

That was something I experienced on a daily basis. It dawned on me that I had jumped into the deep end without my water wings. This was a sink-or-swim moment of massive dimensions. I was not only in the deep end, it felt like I had jumped overboard from the QE2 halfway between Southampton and Ellis Island and my life jacket was on a different cruise liner.

Just as my homesickness was reaching catastrophic proportions, almost an entire week into the school year, I was called to the headmaster’s office. Another Canadian, going to a different school in Norway, had phoned the school and asked to speak with me. Just like me, she had planned to spend a year in the country of her forefathers. She called to tell me she was going home.

“Bon voyage.” I said, “Say hi to my parents.”

I was literally dying of homesickness and figuratively gulping down salty sea water in the mid-Atlantic. That was peanuts compared to giving up and having my mother meet me at the airport saying: “I told you so. You can’t make your own bed, I’m surprised you lasted as long as you did.” My mother is a very kind person, and we’ll never know if she would have said that, but in my paranoid nightmares, that’s all she said.

Sink-or-swim is a great way to learn, especially when you start paddling. Flail those arms, kick those legs, learn to float once in a while but never ever allow yourself to think that you can’t make it.

I started swimming for all I was worth. I would lie in bed at night trying to remember new words. I would try to remember what they meant, and how they were used. I would think about who said them and envision that person saying the word over and over and over. I would try to imitate their voice and whisper it to myself. Pronunciation, accent, cadence, rhythm. Everything was important. Slowly, but still figuratively, my swimming progressed. The drone of sound that was my day-to-day life started to become streams of separate words, many of which I still didn’t understand. Soon enough though, I was catching on to what people were talking about, even if the meaning of every word wasn’t clear. At some point, I was able to use my voice to speak their words.

Today, Norway is a modern, mature market country. English has infiltrated the language and teenagers wouldn’t hesitate to speak English with a foreigner. If you listen to kids there today, you hear a lot of English words even when they’re talking to each other. I know how fortunate I was.

If I had embarked on my gap year in 2018 instead of 1978, I wouldn’t have had the same “fake-it-till-you-make-it” or “sink or swim” challenges, nor the opportunities that overcoming those challenges led to. I also would have been 58 years old which is probably a bit late to start a post-high school gap year.

Stay safe, Always Care

87 stories are part of the Always Care Community newsletters, where we share memories, experiences, and lessons learned at the “University of Life”!

Thanks for reading and for supporting my work.

Please connect to learn more about how our experience and expertise can support you, your team, and your business.

I loved the story, it reads like an adventure (which it was!). You're a great storyteller, Paul! I was there with you all the way, I held my breath, I even want to learn Norwegian now haha.

By the way, I still send postcards and Christmas cards by post. I love this habit.

You started traveling back when it was a REAL adventure. You did it the right away, all in! Good for you. A real inspiration.